THE GALLERY

In the 60’s a brand new art gallery was launched in Lisbon. Its founder, Francisco Pereira Coutinho, chose to call it S. Mamede.

It opened during particularly troubled times, on both national and international levels. Suffice to say that this decade represented the beginning of the Portuguese colonial war and the arrival of the first national student movements, which were basically an omen of the end of the Dictatorship. Furthermore, in parallel with these events, there were the conflicts in Vietnam, the May 68 in France, and the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the troops of the Warsaw Pact.

During the prior decade, the world tried to heal the wounds caused by the Second World War, however they seemed to be very persistent in several parts of the globe. The world was focused on the fights between the new and the old empires such as Indochina, Korea, Vietnam, etc. The old world was trying to resist the new one, and new voices and movements hoping for a better world were sprouting everywhere. Freedom, Equality and Fraternity became more than a myth; Human Rights were finally respected, and moreover, the distribution of wealth and cultural goods became fairer. Ultimately, new ethics and a different moral rose above everything else.

In the old world, and also in what seemed to be the new one, totalitarianisms hunted the citizens, pledges arrested intellectuals and artists merely because dictators disliked everyone who didn’t follow their demands and rules. Free thoughts were considered a threat. Regardless of the threat, political or religious, or both, the temptation of a sole and absolute power has always been hand in hand with Men.

In the decade of 50 in Portugal, visual arts were characterized by a continuous fight between ideological and political factions that were expressed through arts and literature. And the Estado Novo system, strengthen by the position taken during the WWII, tried to establish an international identity, backed up by new spiritual politics; which had always been shadowed by the conservatives.

In 1953, the SNI selected a group of 35 artists and sculptors among the 300 who were not assigned to Salazar’s system. The group was meant to represent the country in the visual arts field, and was composed by the following names: Bentes, Francis Smith, Amadeu de Sousa Cardoso, Santa Rita, Dórdio Gomes, Sara Afonso, Carlos Botelho, Mário Eloy, Júlio, António Pedro, Augusto Gomes, Estrela Faria, João Hogan, José Júlio, Júlio Resende, Sá Nogueira, Fernando de Azevedo, Fernando Lanhas, Jorge de Oliveira, Vespeira, Júlio Pomar, Fernando Lemos, Querubim Lapa, Lima de Freitas, João Abel Manta e Eduardo Luís; e na escultura, Francisco Franco, Canto da Maia, Barata Feyo, Martins Correia, António Duarte, Vasco Pereira da Conceição, Jorge Vieira, Lagoa Henriques e Fernando Fernandes. These happenings brought in a golden result, perdurable such as the bronze, which would be revealed later on.

The existence of several different aesthetic currents and schools caused predictable quarrels between them. Some said there were more fruitful paths to follow than the abstraction or the inconsequent delirium of the surrealists. These used to portray the fights and aspirations of the world, the Franciscan poverty, and the pain of the weak and the winners. Others wanted to push away the pumpkins and onions, the expensive portrays of expensive and beautiful women. Some studied the followers of the supranational artistic cosmopolitism, and therefore had no roots and preferred to get deep into their own surroundings and problems, focused only on the objective conflicts of their own generation.

Clearly the majority of the high bourgeoisie, the ones who had the means to buy art works, were in favor of the system, which meant they only bought either ancient art or they would be sympathetic with the naturalists. Only a few would dare to show any appreciation for the so-called modern art. During the 50’s and 60’s, in Portugal, Picasso was still seen as joke, and practically no one would exhibit those “miscreations” in their houses.

By the end of the 50’s there were a few changes in the art field, the 14 th Exhibition of Modern Art by the SNI, the works of SNBA, Casa Jalco, Galerias de Março, Alvarez, Pórtico, Diário de Notícias and Casa da Imprensa, plus all that was organized in the Faculty of Sciences. Also, in 1947 Mário Cesariny presented the “O Operário” (The workman), an exceptional work that some contemptuously referred to as “O Aranhiço” (The Spider) or “A Borboleta” (The Butterfly), evidencing a desperate affection for the rules and similarities of the realists. In 1953, Cruzeiro Seixas, who had moved to Angola, exhibited his artworks in Luanda, leading to a tremendous scandal. Apparently it was too much Modernism.

It is extremely important and only fair to highlight the rising of the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian in 1956, which was a direct result of the smart efforts of Dr. José de Azeredo Perdigão in getting the donator on board. This institution was responsible for an excellent work in all sorts of fields, especially in what concerns to Fine Arts, by creating the first Museum of Modern Art in Portugal, by doing multiple exhibitions, and by supporting the artists. Also, Dr. Azeredo Perdigão was forced to embark on a tight fight with all the opponents of the museum, which were many. The Gulbenkian Collection together with the specialized library and other services gave a definite impulse to the affirmation of this important sector of the Portuguese Culture.

São Mamede managed to become a meeting point for the members of high society, before and after the April 25th. The most representative visual artists were involved with the gallery, allowing it to form dozens of private collections of modern art. This would help the artists not only to earn enough money to survive in their own country, but also to gain recognition in foreign markets. The São Mamede was very criticized for sponsoring this notion of a market, however, nowadays the stock prices reached in auctions prove that the country couldn’t be left out of this concept and international trend. Many climbed boarders (no need to mention names) and many made a real effort to accomplish it.

Movies, conferences, literary and visual editions and many others had their originals made very popular, having really high prices due to the creation of serigraphs. These were made available for the common stock exchanges, as a way of keeping the doors open for students and any public passionate about fine arts. São Mamede was one of those institutions, which focused on making all sorts of art expressions available to everyone. I made sure I would say this in my statement because only I know the hard work that was necessary to make it happen.

This Portuguese example might be insignificant if we think about François Miterran’s family, in France, which created a true empire of Art Galleries that remained alive after French president’s death, continuing in possession of his family.

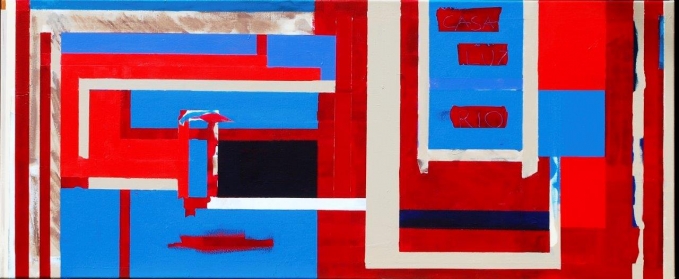

Truth be told, in our country other “marchands” followed this path. Nevertheless, Francisco Pereira Coutinho stood out because he had the subtlety of choosing an incredible space for his gallery, with one of a kind old Pombalin rooms. On top of that, he enriched the enclosure of the building with modern equipment, he made sure he was surrounded by the most qualified professionals and developed and identity for the graphic design of editorial books and catalogs. Moreover, Francisco also ensures that the choice of frame and illumination are the most adequate to enhance the pictorial character of each artwork, being always supported by the best workshops in town, making it possible to create an unmistakable brand for each artist.

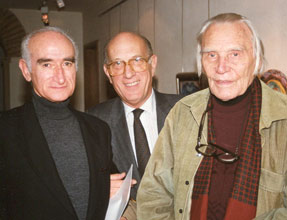

Nonetheless, the moment of his retirement has arrived and, confident in his decision, he passed on his legacy to his son, also Francisco, and two other friends, hoping for a happy sequence of two generations.

Luis d'Oliveira Nunes, February de 2002